Killmonger’s Captive Maternal Is M.I.A:

Black Panther’s Family Drama, Imperial Masters

and Portraits of Freedom

by Joy James

The Audience Speaks

Seeing Black Panther during Women’s History Month, following its Black History Month premier, was not as intense as screening the Marvel movie during its first box office record-breaking weeks. The importance of the film though is determined by the viewers’, black viewers’, emotional need for Black Panther narrative and visuals. In certain theaters, audiences reveal that they are the arbiters of taste and politics.

Last March, in Harlem’s AMC Magic Johnson Theater, where violent “Coming Attractions” last 20 minutes, a few audience members arrived—probably for their second or third screenings—30 minutes after show time. Cell phone flashlights beaming, they searched for front row seats as one irate female shouted “What the fuck are you doing?!” Veterans, the seated audience waited quietly until all could enjoy the film. Audience performance and sensibilities folded into the screen play as adults and children reflected a gentrifying Harlem. Bonded by two hours of entertainment in a cavernous, dark hall, neo-indigenous blacks, latinx, and white settlers sat side by side, embodying the Wakanda promise.

Harlem moviegoers used their capacity to interject personal preferences onto screen characters, rewriting the script with call-response precision. When General Okoye, concerned about CIA infiltration, resisted transporting wounded CIA agent E.K. Ross back to Wakanda after he took a bullet for T’Challa’s beloved Nakia, a man of indeterminate ethnicity hissed “Bitch!”; in a theater filled with black people losing their land, I heard this misogyny on behalf of white police as coming from a settler. Later, when the General pointed a vibranium spear at the vitals of her partner W’Kabi, retorting “Yes” to her rhino-riding lover’s traitorous query as to whether she would kill him to save Wakanda from Killmonger, the woman who shouted “Damn Right!” with the fierce intensity of domestic trauma and betrayal registered as black. When the audience failed to celebrate Killmonger’s death as a victory, they granted a solemnity to his passing, punctuated by one black father’s emotional, guttural articulation of loss. . .collectively the audience was silenced by the gravitas of black rebels, losing unwinnable wars, trapped in Hollywood spectacles.

Killmonger’s crimes were egregious. He was a mass murderer. Yet, the audience seemed ambivalent about Hollywood killing him. It did not noticeably or sympathetically respond to the poisoning of the white female director overseeing African religious and cultural artifacts held hostage in a European museum. Nor was it responsive to Killmonger shooting his femme fatale girlfriend (some commentators were disturbed by pathological, black American “toxic masculinity”; if Killmonger’s deceased lover was also from the U.S., then images of black American “toxic femininity” suggest an ungendered savagery held by U.S. blacks). It was only when a favored Dora Milaje leader stared into the desperate eyes of sister General Okoye, shouting “Wakanda FOREVER!” before Killmonger slit her throat that the audience (me included) gasped. Some of us then felt that Killmonger had lived too long and became impatient for T’Challa to dispatch him in a subterranean vibranium subway. Others might have wished for the Dora Milaje to de-necklace his misogyny and femicide with a beheading. However, Black Panther would not allow Killmonger to be killed by female captive maternals. Only after he hurled the Dora Milaje elite into the battlefield of rogue tribesmen and rhinos, and M’Baku (women) warriors fighting to tilt the balance of power towards T’Challa, only when Killmonger prepared to notch another armor scar by stabbing baby sister Shuri, did T’Challa find the strength to take mortal combat into the underworld.

In arbitration, if there is a debate, the audience determines if this violent coming of age story punctuated by sunny natural beauty is a hero vs. villain fable or a family drama in which alienated and abandoned family members painfully seek re-entry and closure. Maybe it is both. The Harlem audience applauded only at the end of the movie when T’Challa got what he craved more than the throne—the kiss from a sovereign captive maternal, Nakia, who saved his life and gave it meaning. The mythical Panther King was ready to settle down and the audience was ready for its own closure after four epic battles. Family precedes and follows drama. T’Challa earned not a mere throne but kinship with a sovereign captive maternal, a beautiful, brilliant, and compassionate warrior. The Harlem audience as arbiter of taste seemed to relish not a union between Wakanda and the CIA but a restoration of tribe. The former was problematic and potentially deadly given the history of the CIA. The latter, marked by trauma, was shaped by Wakandans whose lives were structured and stabilized by sovereign captive maternals. There was a happy ending because sovereign captive maternals brought the whole man home. The broken man who sought to be king was cared for or abandoned by captive maternals descended from enslaved Africans. Being from Oakland, he would die without honor and without the comfort of a captive maternal, sovereign or enslaved.

Where’s Your Mother (AKA Captive Maternal)?

Upon becoming king of Wakanda, T’Challa visited the ancestral afterlife to find his assassinated father T’Chaka, who reassured him of his capacity to be both King and a decent human with the query: What kind of father would not prepare his son to continue life in his absence? That raises another (unasked) moral and philosophical inquiry: What kind of mother would not prepare her child to live in her absence? One need not belabor the fact that T’Chaka killed his younger brother and abandoned his nephew, foreclosing the father option for young N'Jadaka who would become “Killmonger.” Philosopher Janine Jones raises the query about Black Panther’s villain:“Where is the mother?” I understand that to be a question about the captive maternal, the ungendered but often racialized female, whose function and labor provide emotional and material support that furthers communal and familial stability. So,who is raising that boy?

The interrogation of black children, often read as black boys (Black Panther erases girls and queered communities from the screen) raised in privatized sites or state wards is “Where’s your mother?” Non-sovereign captive maternals seem to be stigmatized as more flawed than sovereign captive maternals; masters and mistresses fed and feed on the reproductive and productive labor of the non-sovereign whose generative powers are used against them and who function as stabilizers—until grief, trauma, or violence lead to breakdowns, rebellions, and disappearances. Sovereign captive maternals such as the Wakandan women were never slaves or exploited laborers; it doesn’t appear that they were ever poor or ever raped. Their “captivity” resides in a network of emotional circuits of care, seeking the well-being of those they love. They move like Queens on the chess board protecting a sometimes limited King.

N’Jadaka is renamed by his CIA foster family’s rift on “warmonger,” because he is missing his captive maternal. Without a sovereign Wakandan maternal—his aunt Queen Ramonda, cousin Shuri, the female warriors—the youth desperately needs an Oakland mom; one who could find airfare to Wakanda, or call the Queen to negotiate sending the boy to his father’s side of the family for healing and raising despite fratricide. A captive maternal would have tried to support a traumatized youth as a revolutionary or appeaser. Failing to steady him on some path tied to community, the maternal could mutter as griot: “Look at what they did to my baby.” A black mother or grandmother, Wakandan or Oakland, could have minimized family trauma. Losing your mother is traumatic; but so is losing your child.

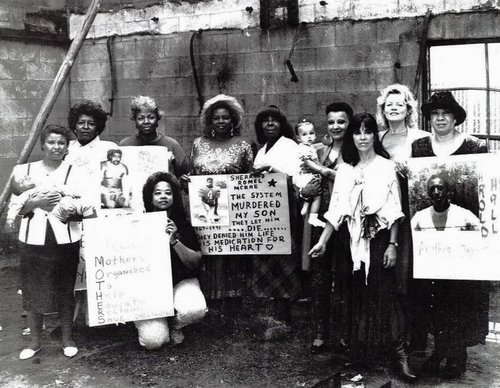

Members of the Los Angeles organizing group Mothers Reclaiming Our Children

N’Jadaka’s paternal grandmother, on screen, could have made King T’Chaka go back to the U.S. and get her grandson. The grandmother would have foreseen U.S. foster care, imperial armies, pernicious institutions, and unbridled aggression. She would have understood the plight of raising grands with damaged, missing, incarcerated, or dead parents. Grandmothers are bio-vibranium; partnered with the meteorite that took all of the credit for the wonders of Wakanda, they could have resurrected the near-dead. T’Chaka’s mother could have stood down Queen Ramonda to rewrite the prodigal son narrative to make the absent Oakland mother the heralded returnee; conspire with male captive maternal Zuri, who witnessed the killing of Killmonger’s father, to contain, heal, or dispatch Killmonger, who throttled a female elder healer who attempted to preserve life-giving herbs.

Missing his own mother, N’Jadaka’s father lost an ally and emotional anchor. He also inexplicably lost the mother of his son. Perhaps N’Jadaka’s mother was a revolutionary captured or killed in battle. Perhaps she was migratory or indifferent. The sensitive, suffering, proud, and ethical father of N’Jadaka likely partnered with an equal to create a child he loved yet would not be allowed to raise.

The Fifth Column

The “fifth column” is the enemy within one’s own ranks. Without a community of maternals fighting for justice, Killmonger’s vulnerabilities will inevitably defeat him. Killmonger has no captive maternals; they are M.I.A., missing in action. Off screen, one can recall nonfictive maternals as an antidote to the limited imagination of Hollywood film. Mamie Till Mobley defied norms with an open casket funeral for 14-year-old mutilated Emmett declaring: “I want the world to see what they did to my baby.” Assata Shakur, framed by the FBI-CIA and police, shot, tortured, and jailed, gave birth to her daughter while imprisoned and then escaped to see her child outside of captivity. Erica Garner spent her last months and breaths in 2017 loving her children and protesting the NYPD homicide-murder of her father, Eric Garner. Brazilian councilwoman and activist Marielle Franco, a black lesbian mother who resisted police brutality and the paramilitary in favelas, was politically assassinated in 2018. The revolutionary persona of any one of these women is compatible with resistance and justice. The absence of their prototypes in popular film suggests an absence of resistance that seeks liberation.

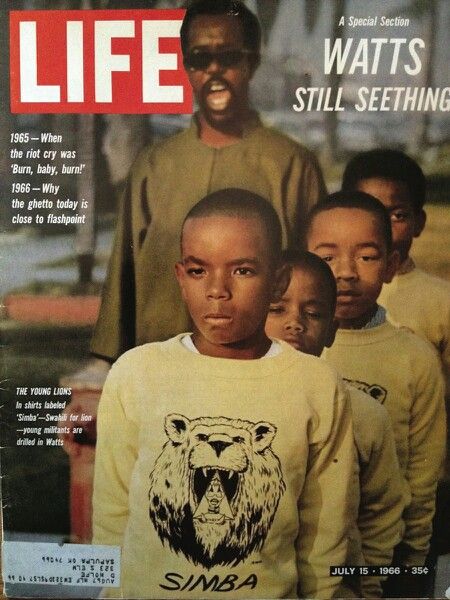

Emmett and Mamie

When the only black American dies in Black Panther’s final apocalyptic battle, it signals a time for reparations. The Wakandans will export justice to the world with their wealth of technology and wisdom. They will start in Oakland. The confidence or conceit is that Wakanda can outplay the CIA. The royal siblings’ first mission is to Killmonger’s birthplace. Unlike Harlem, they not settlers will gentrify Oakland as T’Challa’s first political act is to buy real estate. The child who approaches him on the Oakland basketball courts that N’Jadaka played on years earlier looks like a young N’Jadaka with braids. He distinguishes himself by leaving the other black boys—no girls are in the yard, perhaps they are at home taking care of younger siblings—who admire and contemplate jacking the hoover craft as Shuri explains mechanics and theoretical physics. The N’Jadaka look-alike walks away from technology towards the man who brought it. Understanding power and his own inherent sovereignty, this is his playground, he boldly asks the king for his identity. T'Challa responds with a secretive smile different from the one given to the CIA agent: here there is mutual recognition not deception.

Until his mother or sister calls him home for dinner, this boy will be a Wakandan subject-warrior, in an expanding protectorate of promised technology and training to safeguard against predatory police, poverty, and carceral education. Every child left behind, reintegrated, and educated into a protectorate, is promised Afrxfuturity without special ops and empires, built upon the backs and with the bones of Africans who would or could not jump ship.

Black Panther lets T’Challa offer black Americans an alternative to Killmonger’s final wishes: “Bury me in the ocean so that I can be with the ancestors who jumped ship.” N’Jadaka-Killmonger commingles with ancestors who jumped ship rather than be slaves. If the fifth column outmaneuvers the Wakandan promise via technology and billionaire-style investments, renegades and fugitives will survive in waters where molecular particles mingle the oceans of ancestors, Haitians, Nigeriens, Syrians falling or pushed over the edge, as Christina Sharpe reminds us.

The ancestors will embrace the lineage they created. Perhaps their fifth column within racial capital and conquest is the captive maternals. For it was the powers that sovereign maternals gave to T’Challa that allowed him to live long and painfully enough to become a true king. A loving mother, sister, fiancée, and general amplifying the emotional, intellectual, and physical lives of men and the ungendered—all captive maternals with capacity to save CIA agents and if necessary in the future save themselves from the CIA. Everyone’s powers would be amplified by having kinship with captive maternal love and sacrificial labor. Ask King T’Challa. Better still, ask his American cousin.

Note

Captive Maternal is explored here: James, “The Womb of Western Theory: Trauma, Time Theft, and the Captive Maternal” (Carceral Notebooks, 2016, http://www.thecarceral.org/cn12/14_Womb_of_Western_Theory.pdf).

ARTICLES

The Courage to Invent the Future

Killmonger's Captive Maternal Is MIA

Eulogy for Wakanda/The King Is Dead

What Don't Make Dollars Don't Make Common Sense

Dream Work: Fantasy, Desire and the Creation of a Just World

A Crisis in Hollywood: Black Panther to the Rescue?